A personal memoir by Benjamin Bergery

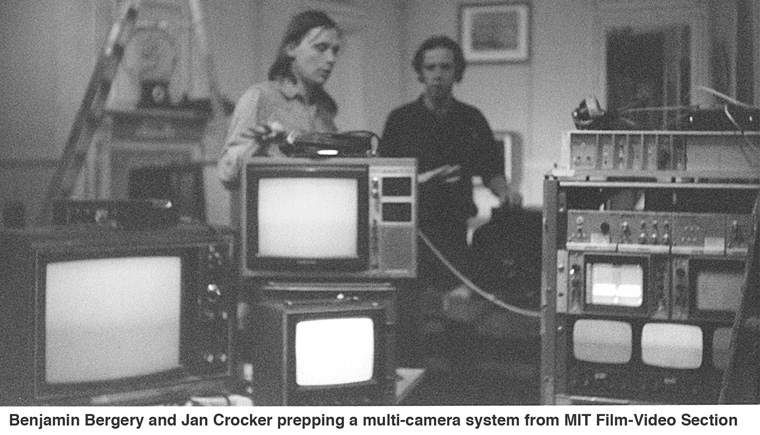

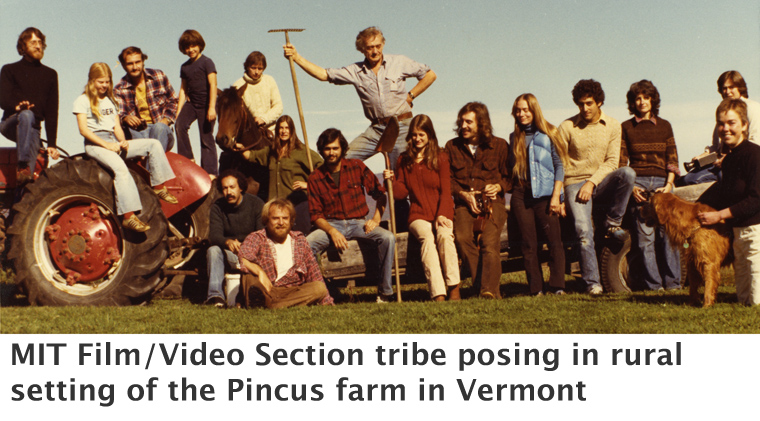

Most of the videos of live Boston music on this site were produced by myself and Jan Crocker from 1979 to 1982 with people from the MIT Film/Video Section. These multi-camera videos were mostly shot in the framework of a course I taught over many semesters at the MIT Film/Video Section entitled Film, Video and Performance. The choice of bands to document was curated and organized by Jan Crocker, who had a keen sense of the post-punk musical revolution underway locally, and in the UK.

For me, the culmination of this endeavor occurred when we shot The Cure on the dim, tiny, ground-level stage of the Underground nightclub. I will always remember standing three feet next to Robert Smith, shooting him with our custom black and white shoulder-mounted Newvicon camera. The other camera people were Jan Crocker and Rachel Strickland.

It was the first time I ever heard The Cure, and their music entranced me, and my camera. We had a technical problem with our video switcher, but our engineer Terry Lockhart came up with the brilliant alternative of encoding our three cameras together in a striking red green, blue and gray composite image. It was one of those rare moments of grace when the music, camerawork, and video effect all blended together beautifully.

Of course, this moment of grace was made possible by the dozens of live video concerts that preceded, many of them less evolved learning experiences. The multi-camera footage of this series of videos was mostly shot by MIT students, many of who are listed below. I also shot, and sometimes operated the video switcher, as did Jan.

Thankfully, Jan preserved the original 3/4 inch video cassettes, and spent many hours editing them during the 1990s to create the finished videos on this site.

+++

Vérité Performance

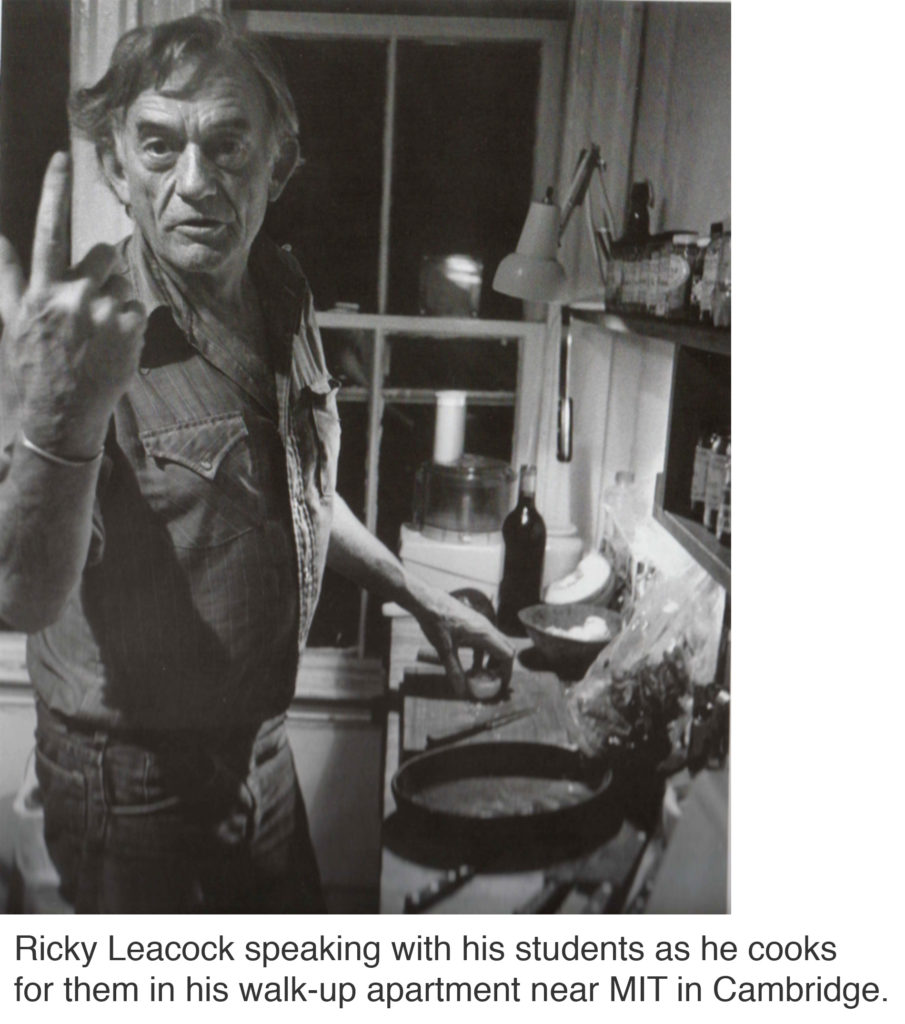

The MIT Film/Video Section was defined in great part by the cinéma vérité documentary approach pioneered by my mentor, the late Ricky Leacock and others in the 1960s.

The idea of cinema vérité was to shoot events with as little interference as possible. I will always remember the 3 shooting rules that Ricky gave us in my first class at MIT:

1. No tripods

2. No lighting

3. No interviews

(I also remember my very first job as a cameraman after graduating, when the TV news producer came up to me and said: “Why don’t you set up the tripod and lighting over here so we can shoot the interview.”)

These live videos were greatly inspired by Ricky Leacock — who directed the Film/Video Section, and led the first edition of the Film, Video and Performance course with me. Ricky screened some of the early films he shot – many with his close collaborator D.A. Pennebaker — including music documentaries like Jazz Dance, A Stravinsky Portrait and Monterey Pop, as well as dance documentaries like Company and Tread. Watching the exquisite camerawork of Ricky and Penny taught me how to shoot performance.

Another, earlier inspiration was the late Ann McIntosh, who led the first video class at MIT, with me as her teaching assistant. Ann brought her New York theater background and encouraged student camera people to shoot in the moment, to improvise like actors on a stage. Ann taught me that shooting is also a kind of performance.

All the music performances were shot handheld using existing lighting, in the cinéma vérité tradition. So the approach to camerawork in the music videos was inspired by a mix of the classic vérité documentary, and a feeling that the camera person is participating in the performance he or she is shooting — which is kind of the opposite of cinema vérité. I tried to transmit to my students this idea that shooting, like dance, was a mixture of acquired skill and improvisation. My friend and fellow MIT videomaker Bernice Schneider brought a similar approach to shooting classical and modern dance.

+++

Vérité & Video Art & New Wave

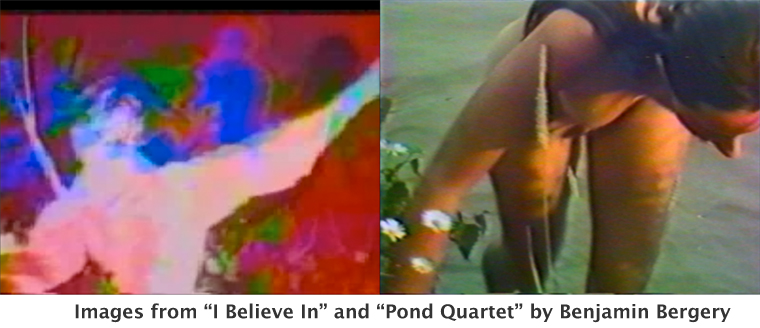

In addition to documentary, the MIT Film/Video Section also became a center for early video art in the 1980s, notably in courses I led that mixed MIT engineering students with art students from the Boston Museum School and MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies. I built on my previous experiences with the WGBH New Television Workshop, and my mastery of its Paik/Abe analog video synthesizer, to nurture a painterly practice of video effects combining several video images on the screen.

Future artists who attended courses at MIT Film/Video include Jim Campbell, Luc Courchesne, Pat Hearn, Michael Naimark and Bill Seaman. I also contributed video art pieces that earned me some awards and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Massachusetts Council for the Arts. My final art project at MIT was Elastic Movies, a poly-linear, interactive art videodisc that I produced with a class I taught: Workshop in Elastic Movie Time.

So the music videos I made with Jan can be seen as the intersection of several very different aesthetic approaches: cinéma vérité, video art and the post-punk and new wave music movements, as represented by a mixture of local and British bands performing in Boston clubs.

The handheld, cinema vérité approach was well suited to the raw energy of some of the Boston post-punk bands, and the ambience of the clubs; we camera people were often right next to the band on stage, giving a distinctive intimacy to the images. Layered multi-camera electronic imagery was also a good complement to the British invasion of moody new wave bands.

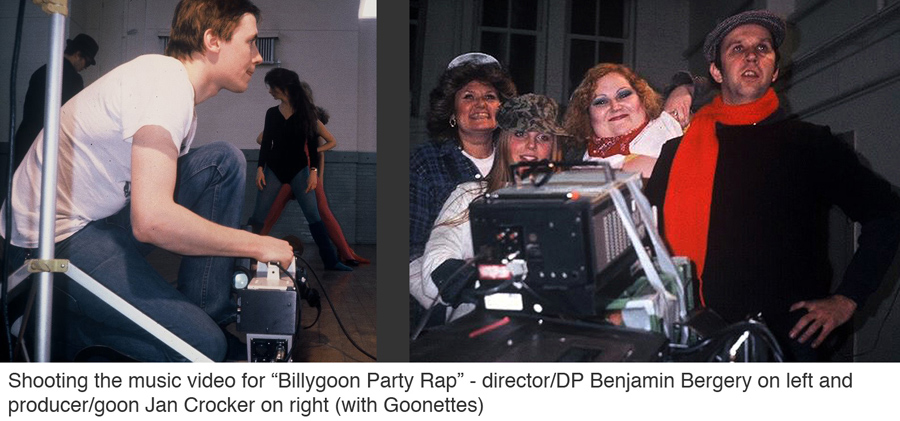

The music videos were also the result of the complementary collaboration I had with my friend Jan Crocker, which was based on mutual respect and a shared experimental aesthetic. Other experiments of that time include the professional concert video that Jan and I produced of Human Sexual Response (with the help of my friends Jay Heard and Don O’Sullivan at Multivision), and the light-hearted music video I directed with Jan’s rap group, The Fabulous Billy Goons.

+++

Technological Innovation

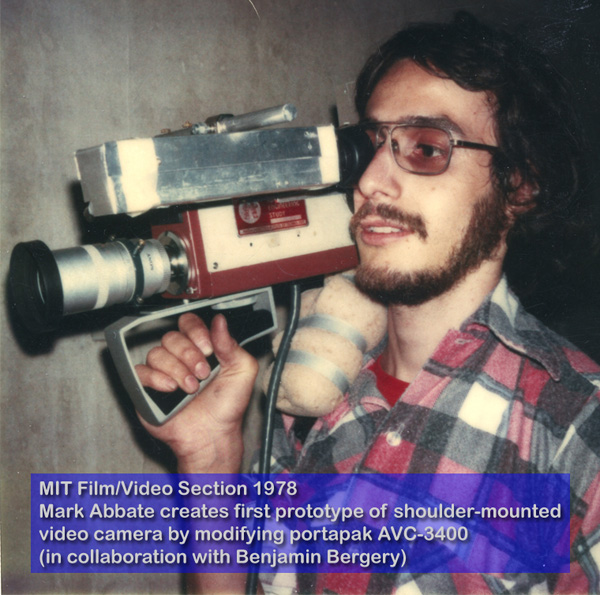

Video is a technological art form, and the video work here is partly defined by the pioneering innovations of MIT Film/Video Section engineers Mark Abbate and Terry Lockhart, who helped define the mobile systems that allowed us to shoot handheld multi-camera video in dark clubs without any additional lighting, which would have impossible with any other camera of the time.

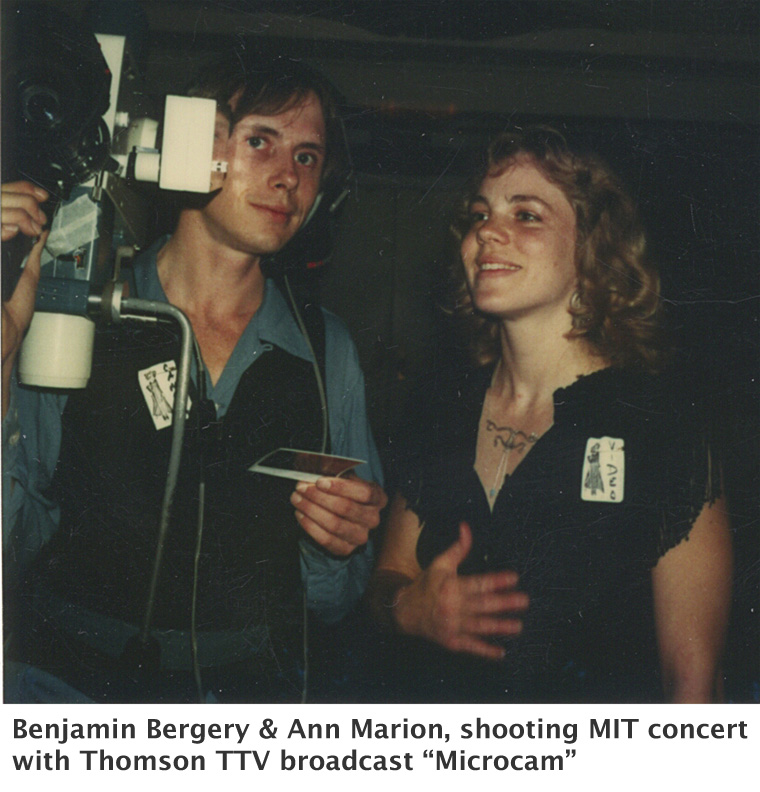

At the time, professional broadcast video involved huge three-tube cameras the size of small refrigerators. Even the most compact cameras, like the Thomson TTC Microcam, where the camera’s head was separated from its electronics by a thick cable, required a clunky belt and rod support. Worst of all, these cameras required thousands of Watts of light to yield an image.

In the late 1970s, MIT Film/Video Section engineer Terry Lockhart began replacing the black and white Vidicon tubes in Sony Portapak AVC-3400 cameras with Newvicon tubes, which could shoot in extremely low-light conditions, like night clubs. Because of their infra-red sensitivy these cameras could see in the dark!

In 1978, I aided and abetted MIT student Mark Abbate who built the first ever lightweight shoulder-mounted video camera. Mark modified Sony AVC-3400 and AVC-3450 cameras – removing the video monitors used as viewfinders and placing them outside so the camera could be on the shoulder. These modified low-light black and white cameras enabled us to shoot handheld in any Boston club, with light levels that were far too low for other video or film cameras.

Other key technologies for the Project included sync generators, and the elegant Shintron 370 video special effects video switcher manufactured in Cambridge by MIT graduates. Terry Lockhart also introduced a video encoder to the mix of tools, allowing for combining different cameras for the red, green, blue and luminance signals, notably in the stunning compositions of The Cure video. When Jan Crocker organized the shooting of a Fashion Show at the Spit club, MIT camera people shot the event with a mix Super-8 mm and video, two humble tech tools that intercut well.

+++

Credits

The music videos were made possible by the involvement of many people at and near the MIT Film/Video Section including:

Ann Condon, Ann Marion, Barbara Costa, Beanie Jay, Benjamin Bergery, Bennett Leeds, Bernice Schneider, Bill Topazio, Burt Rosenberg, Dan Franzblau, Daryl Desmond, Diane Bohl, Don O’Sullivan, Don Schaefer, Gloriana Davenport, Hannah Silverman, Harris Eigabroadt, Jan Crocker, Jay Heard, John Chittick, John Newton, Karine Hrechdakian, Kathy Izzo, Ken Safire

Larry Gallagher, Lynn Cruickshank, Mark Abbate, Michael Roper, Moe Shore, Nancy Elrick, Norman Lang, Pat Hearn, Paul Rachman,Peter Hutton, Rachel Strickland, Richard Leacock, Rick Harte, Scott Lindberg, Shelly Lake, Terry Lockhart, Tom White

+++

+++

+++

Historical Footnote: From MIT Film to MIT Film/Video

The MIT Film Section was started informally before my time there by documentarian Ed Pincus, with a focus on 16mm synch-sound filmmaking. MIT President Jerome Wiener then invited Ricky Leacock, one of the founders of cinema vérité, to head the educational unit which was housed in MIT building E21.

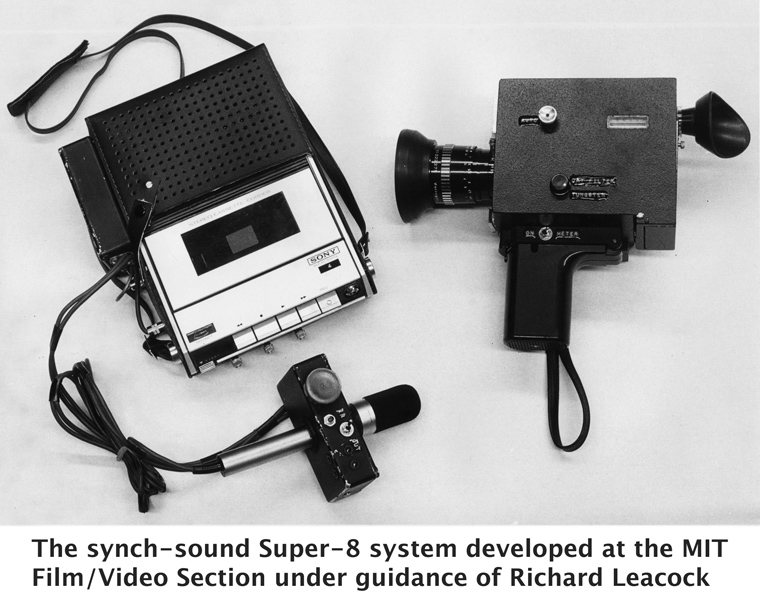

Ricky’s first major project at MIT was to spearhead the development of double-system Super-8mm camera and cassette recorders. The idea was to create a smaller, cheaper version of 16mm systems. Because these cameras were cheaper and smaller, they encouraged humbler and more playful projects than the expensive 16mm tools. This is a good example of the interplay between art and technology that underlies a technological art form like filmmaking.

When another MIT department donated a Sony 3400 Portapak system to the Film Section, I passionately adopted this brand-new electronic tool, which I saw as the technology of a new era. Soon, there were several of these ½ inch Portapaks at the Film Section, and I ended up teaching introductory courses that included both Super-8 and ½ inch black and white video.

As our video tools grew, I became the Film Section’s video specialist and teacher, first as graduate student, then as an Instructor and finally as a Lecturer. At the same time, there developed an “upstairs/downstairs” cultural divide between video and film, between those shooting ambitious vérité documentaries in 16mm with budgets of thousands of dollars, and those of us shooting more modest hundred-dollar video projects that sometimes veered towards video art.

After a few years, I pushed for changing the name of our unit to the “MIT Film/Video Section”, with the support of my fellow teachers and friends Glorianna Davenport and Rachel Strickland; we urged students to refer to “movies” instead of “films” or “videos”. Ricky gave his blessing to this new name for our unit, and we actually changed the letterhead. Although much of the “video art” direction was not to his taste, Ricky realized the importance of video, and his generous nature encouraged us to pursue our video projects.

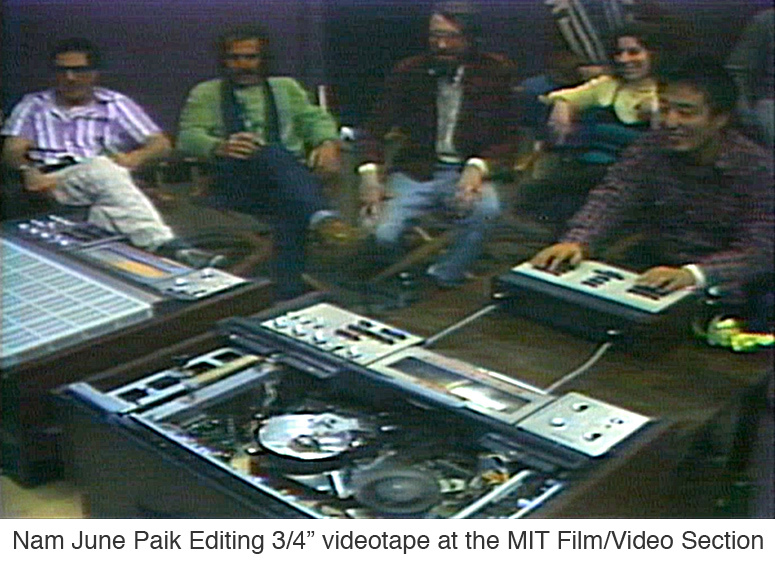

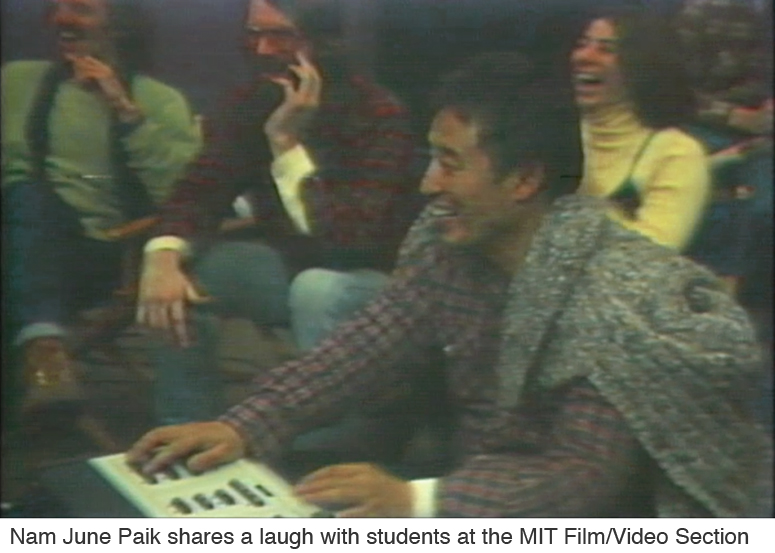

Ricky helped us by bringing in avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas, and, later, I organized a visit by Nam June Paik, both moviemakers left a deep impression on some of us. Jonas Mekas made diary films by shooting spurts of 16mm film with his hand-wound Bolex camera, often not looking through the viewfinder, but just pointing the camera. From him, I learned that shooting could be a painterly gesture, and a film a series of poetic strokes. Nam June Paik taught me a form of rhythmic jump-cut editing that could be both sculptural and musical. I now realize that both of these very different masters taught me cinematic cubism.

To be honest, “Film/Video” was never really accepted by many of the graduate 16mm filmmakers, and there was a cultural divide, with anthropological, sometimes political, 16mm documentaries on one side, and video “pieces” on the other. That’s not to say that the works of, say, my friends Steve Asher, Mary-Jane Doherty and Michel Negroponte weren’t valid and important, just that they were different in tone and genre from the video works. My friend Moe Shore documented a series of musical performances in 16mm, which I helped shoot. A theme that was shared by some 16mm and video shooters was the autobiographical, diary genre.

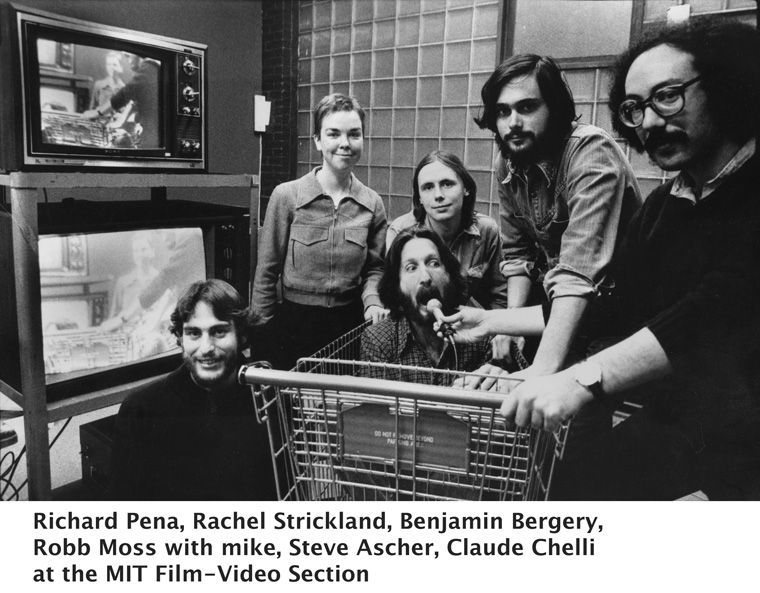

The diary genre was pioneered at the Film Section by Ed Pincus, who shot a multi-year 16mm diary with a wonderfully ironic title: Life and Other Anxieties. Other early diarists included Jeff Kreines, who worked in the equipment room, and later shot Seventeen with Joel Demott. Other film diarists include Mark Rance and Ann Schaetzel. I also made a series of autobiographical videos, the most accomplished were Young August, and Pond Quartet (dedicated to Ricky Leacock). My fellow student Robb Moss made a beautiful documentary of a trip with a group of friends down the Rio Grande. The most commercially successful diarist was Ross McElwee who made the theatrical hit, Sherman’s March. Richard Pena went on to direct the New York Film Festival, while Claude Chelli became an influential French television producer.

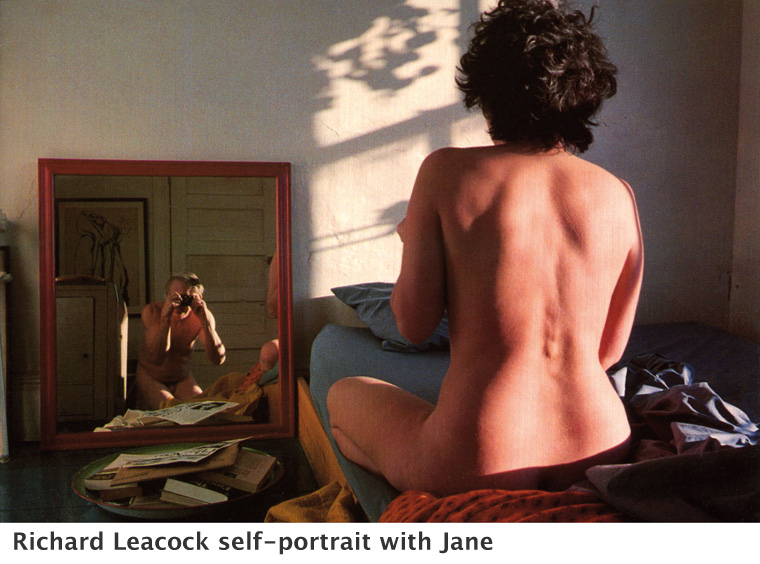

Autobiographical filmmaking was the opposite of traditional vérité: while the vérité filmmakers of the 60s sought to be as invisible as possible, the diary filmmakers did the opposite and became the subject of their films. Although Ricky Leacock made a sweet Super-8 film entitled Visit to Monica, chronicling his visit with the widow of his mentor Robert Flaherty, I believe he never really subscribed to the autobiographical genre. While he was at MIT, Ricky’s most autobiographical work was his wonderful photography, shot with his small beloved Minox camera.

At MIT, we often discussed the “Heisenberg Principle” of documentary filmmaking: the camera changes the filmed subject, sometimes a lot, sometimes a little — less if the filmmaking wasn’t the most important thing happening in the room. Ricky came up with a more graceful phrase for our approach: “shooting events as they happen in the presence of a camera”.